Show results for

Explore

In Stock

Artists

Actors

Authors

Format

Condition

Theme

Genre

Rated

Label

Specialty

Decades

Size

Color

Deals

- MLB The Show

- Featured Books

- New Release Books

- Featured Collectibles

- Youtooz

- Deal Grabber

- Deal Grabber-Action

- Deal Grabber-Anime

- Deal Grabber-Horror Scifi

- Deal Grabber-TV

- Deal Grabber Music

- $9.99 and Under Music Sale

- $9.99 and Under Movies Sale

- 50%-69% off Music Sale

- 70% or more Music Sale

- 50%-69% off Movies Sale

- 70% or more Movies Sale

- 4K Ultra HD Sale

- 88 Films

- 88 Films Sale

- Abkco Label Sale

- Abysse America

- Acorn Media

- Ad Icon

- Adult Animation Sale

- Agatha Christie

- Albums and Artists with numbers sale

- Alien Fan Shop

- Alison Krauss Sale

- Alternative Rock sale

- AMC RLJ Studio

- Amherst Records Sale

- Anime Collectibles

- Anime Toys

- Apparel Accessories

- Aquaman

- deep arcade1up counter cades

- Arcade1up holiday sale

- Arch Enemy on sale

- Arrow Video on sale

- Assassins Creed Shadows

- Deep Atelier Yumia The Alchemist Of Memories

- Attack on Titan

- Audio Technica

- Audiobooks

- Avatar Air Bender Fan Shop

- Avatar Fan Shop

- Avatar The Last Air Bender

- deep axe heaven

- Baby Boomer Sale

- Bandai Collectible Figures

- Banned Books

- Banpresto

- Barbie Fan Shop

- Batman Day

- BBC Sale

- Bear Family Records Sale

- Beast Kingdom

- Beetlejuice

- Behemoth on sale

- Big Fudge Sale

- Bionik

- Black Country, New Road sale

- Black Panther

- Blowout Bin

- Blowout Bin Games Button

- Blue Elan Records Sale

- Blue Underground

- Blues New Release Blues Sale

- Bluetooth Headphones

- Bluetooth Speakers and Components

- Bluetooth Turntables

- deep blu-ray buy more save more sale

- Board Games

- Bob's Burgers

- deep book blowout bin

- Bookazines

- Books Art and Photography

- Books Best Sellers

- Books Box Sets

- Books by Genre Button

- Books Childrens

- Books Coming Soon

- Books Contemporary Fiction

- Books Manga

- Books New Releases

- Books Nonfiction

- Books that Rock

- Borderlands Fan Shop

- Bravado

- Buda Musique Label Sale

- Budget Under 10

- deep business and politics books

- deep cellar live label sale

- Chainsaw Man

- Charley Label Sale

- Chronicle Books

- Chrysalis Label Sale

- Classic Albums For Your Collection

- Classical New Release Sale

- Cleopatra Records sale

- Cohen Media Group

- Comedy sale

- comedy sale

- Compuexpert

- Country New Release Sale

- Country Sale

- CP pre order

- Criterion Collection

- daddario

- Dark Crystal

- Dark Horse

- Dark Horse Comics Collectibles

- DC Comics

- Deadpool X Men Fan shop

- Deadpool X Men Fan Shop

- Deafheaven on sale

- deep all star wars world

- deep funko cartoon blitz

- Funko Gold Series

- deep funko pins

- deep gpo electronics

- deep hasbro games shop

- deep hasbro star wars vintage

- deep spider man fan shop

- Demon Slayer

- Diggers Factory label sale

- Disney

- Doctor Who

- Dragon Ball

- Dragon Ball Z

- Dreamgear on sale

- Dreamworks Sale

- Dune Fan Shop

- Dungeons and Dragons

- Dying Victim Label Sale

- Earbuds

- Ekids Electronics and Accessories

- Elton John & Brandi Carlile on sale

- Elvis Presley Fan Shop

- empire distribution label sale

- Epitaph sale

- Exclusive Bundles

- Factory Entertainment

- Fan Favorites Movie Sale

- Fan Favorites Music Sale

- Fantasy Sale

- Featured Vinyl

- FiGPiN

- Film Collectibles

- Film History Books

- Fisher Price

- Fitness Accessories

- Fitness Accessories

- Five Nights at Freddys Fan Shop

- Fleetwood Mac sale

- Folk Music Sale

- Friends Fan Shop

- Fun City Editions

- Fun City Editions Sale

- Funimation

- Funko Action Figures

- Funko Apparel

- Funko Bitty Pop

- Funko Cartoons

- Funko Comic Book

- Funko Directors and Icons

- Funko Fusion

- Funko Holiday

- Funko Minis

- Funko Pop N Buddy

- deep retro toys funko

- Funko Rocks

- deep funko soda

- Funko Urban

- Funko Video Game

- furby sale

- Furyu

- Galactic with Irma Thomas sale

- Game of Thrones Sale

- deep games blowout bin

- Gemini Sound sale

- Ghost on sale

- Ghostbusters

- GI Joe Fan Shop

- Godzilla

- Golden Girls

- Gonzo Distribution Sale

- Good Smile Company

- Good Time Inc Sale

- Grateful Dead sale

- Great Deal on Games

- Great Eastern Entertainment

- Grindhouse Releasing

- Guardians of the Galaxy

- Hachette

- Hallmark

- Halo Fan Shop

- Handmade by Robots

- Hard to Find Music

- Hardcover Books

- Harmonia Mundi Sale

- Harry Potter Books

- Harry Potter Universe

- Hasbro Marvel Legends Collectibles Sale

- deep hasbro shop

- Hasbro Transformers Studio Series

- HBO Specials

- Headphones

- Hindsight Records

- Hocus Pocus

- Holiday Collectibles

- Hori Nintendo

- Horror Collectibles

- Horror Collectibles

- Indiana Jones Fan Shop

- Inner Knot Label Sale

- Insights Editions

- ION Audio sale

- Jada toys

- James Bond Fan Shop

- Jay Records label sale

- Jazz New Release Sale

- Jazz Sale

- Jensen on sale

- John Pardi on sale

- Journals

- JSP Records Sale

- Jujutsu Kaisen

- Jurassic Park Fan Shop

- JVC Headphones

- Kanto Speakers Sale

- Kidrobot

- Kids and Family Sale

- kids music sale

- Klanggalerie Label sale

- Kotobukiya

- KPop Sale

- L.A. Guns on sale

- Latin New Release Sale

- Lava Lamps on sale

- LEGO

- Lightyear Video

- Deep Lilo and Stitch Fan Shop

- Lion King Fan Shop

- Little Buddy Super Mario

- Little Mermaid Fan Shop

- little people Fisher Price

- Loki Fan Shop

- Looney Tunes Fan Shop

- Loungefly

- Loyal Subjects

- mc records label sale

- Machine Head on sale

- Mack Avenue Label Sale

- Made In Germany Label Sales

- Magic the Gathering

- Marvel

- Marvel Venom

- Mascot Records Sale

- Masters of the Universe

- Matrix

- Mattel

- Mattel Barbie

- Mattel Games

- Mattel Hotwheels

- Mattel Toys

- Maxwell Audio Sale

- McFarlane Toys

- Medicom

- Megahouse

- Memphis May Fire on sale

- Merrithew Fitness

- Metal New Release Sale

- Mill Creek Entertainment

- Minecraft Shop

- Ministry on sale

- Moleskine Journals

- Monogram

- Monster High Fan Shop

- Moribund Records Sale

- Movie and TV Tie-In

- Mugs and Cups

- mumford and sons sale

- music collectibles

- Music Under Ten Sale

- MVD Avantgarde Label Sale

- My Arcade

- My Hero Academia

- Napalm Records Sale

- Naruto

- Naxos Label Sale

- NBA Fan Shop

- Neca

- Needles and Cartridges

- Neil Gaiman

- Netflix Fan Shop

- New Release Video Games

- New Releases

- Nightmare Before Christmas

- Nintendo Accessories

- Nintendo Switch Games

- Nuclear Blast Metal Sale

- Numbers in the Name Sale

- numskull

- Olive Films

- One Piece Fan Shop

- One12

- Onyx on sale

- Orange Rouge

- Overwatch

- Paladino Music Sale

- Paperback Books

- Paramount 4K Ultra HD Sale

- paramount presents

- Pat Travers on sale

- PC Games

- Peanuts Fan Shop

- Peppa Pig

- Persona

- Pinecastle Records Label Sale

- Pink Floyd Sale

- Planet Waves

- Playmobil Sale

- PlayStation Accessories

- PlayStation Games

- Pokemon

- Pop & Power Pop Sale

- Pop Culture Home and Office

- Power Rangers

- Powerhouse Films

- Pyramid Home Decor and Accessories

- Quantum Mechanix

- Quarto Books Sale

- Rap and Hip Hop New releases

- RE Zero

- Real Gone Music Sale

- Rebel Records sale

- Refurbished Video Games

- Religion and Spirituality

- Renaissance Label Sale

- Rhythm Bomb Records Sale

- Rick and Morty

- Ripple Music Label sale

- Robert Hunter sale

- Robin Trower on sale

- Rock Candy Records

- Rock Legends Sale

- Rock New Release Sale

- Rocksax

- Rolling Stones ABKCO sale

- Ronin Flix Films

- Sandpiper

- Scream Factory

- Sega

- Seinfeld

- Sepia Records Sale

- deep sesame street fan shop

- Severin

- Shang Chi Fan Shop

- Shout Factory

- Shout Select

- Shudder Studio

- Singing Machine

- Smith-Kotzen on sale

- Smithsonian Folkway sale

- sonic the hedgehog

- Sony Blues and Jazz on Sale

- Sony Classical on Sale

- sony latin sale

- Sony Rock and Pop Sale

- Sony Soul

- Sony Soundtracks on Sale

- Sony Vinyl on Sale

- Soul R+B new release sale

- Sound Pollution Records Sale

- Soundtracks New Release Sale

- Sparks on sale

- Speakers and Components

- Spin Doctors on sale

- SpongeBob Squarepants Fan Shop

- Sports Collectibles

- Star Trek

- Star Wars Funko

- Star Wars on Sale

- Steelbook Films and TV

- Stephen King

- Stony Plain Records Sale

- Storm Collectibles

- Stranger Things

- Studebaker

- Studio Ghibli

- Studio Sportlight VCI Video

- Studio Spotlight Altered Innocence

- Studio Spotlight Arrow

- Studio Spotlight Bleiberg Entertainment

- Studio Spotlight Blue Underground

- Studio Spotlight Cheezy Flicks

- Studio Spotlight Cult Epics

- Studio Spotlight Decal Releasing

- Studio Spotlight Filmrise

- Studio Spotlight Full Moon

- Studio Spotlight Kit Parker Films

- Studio Spotlight Liberator Films

- Studio Spotlight Main

- Studio Spotlight MVD Film Masters

- Studio Spotlight MVD Rewind

- Studio Spotlight MVD SRS Cinema

- Studio Spotlight Powerhouse Films

- Studio Spotlight Radiance

- Studio Spotlight Smore Entertainment

- Studio Spotlight Troma

- Studio Spotlight Unearthed Films

- Studio Spotlight Wild Eye Releasing

- Sundance IFC Studio

- Sunset Blvd Label Sale

- Super Mario Brothers Fan Shop

- Super7

- Supernatural

- Synapse Films

- Tabletop Games

- Taschen Books

- The Boys Fan Shop

- The Darkness on sale

- the mandalorian deep sale

- The Mars Volta on sale

- The Simpsons Fan Shop

- The Smithereens sale

- The Umbrella Academy

- The Walking Dead

- Threezero

- Thundercats fan shop

- TinyTan Collectibles

- Titan Entertainment

- TMNT Fan Shop

- Tolkien

- Tom Petty

- Tommy Boy Entertainment

- Toy Story Fan Shop

- Transformer Fan Shop

- trapeze label sale

- Trick or Treat Studios

- Tubbz

- Turntables

- Turtle Beach

- TV Collectibles

- TV Complete Series Sale

- TV Favorites Funko Collectibles

- Twin Peaks

- Twinkly Lights

- ultraman

- Underoath on sale

- Universal Monsters

- universal music sale

- Universal Specials

- Universal TV

- Vader on sale

- Van Halen on Sale

- Vertical Entertainment

- Vestron Video

- Victrola Sale

- Video Game Collectibles

- Video Game Merch

- Video Game Plush Collectibles

- Video Game Soundtracks

- Vinegar Syndrome

- Vinyl Accessories Sale

- Vinyl Accessories

- vinyl sale

- Vinyl Styl

- Vinyl Styl

- VP records label sale

- Warhammer Fan Shop

- Warner Archive

- Warner Bros Specials

- Warner Classics

- Watchmen

- Westworld

- Weta Workshop

- Wicked Fan Shop

- Willow Fan Shop

- Winning Moves

- Witcher

- Wonder Woman

- deep wonder woman

- WWE

- Blu-ray 3D Movies Sale

- XBox Accessories

- XBox Games

- Yep Roc Label sale

- Studio Spotlight Classicflix

- Studio Spotlight Gravitas Ventures

- Studio Spotlight Voltage Films

- Studio Spotlight-BBC

- Studio Spotlight-Cinedigm

- Studio Spotlight-Distribution Solutions

- Studio Spotlight Dreamworks

- Studio Spotlight-E1

- Studio Spotlight Focus Features

- Studio Spotlight-HBO

- Studio Spotlight-Kino

- Studio Spotlight-Lionsgate

- Studio Spotlight MGM

- Studio Spotlight-MHZ

- Studio Spotlight-Mill Creek

- Studio Spotlight-Music Box

- Studio Spotlight-NCircle

- Studio Spotlight New Line

- Studio Spotlight-OCN Digital Distribution

- Studio Spotlight-Olive Films

- Studio Spotlight-Paramount

- Studio Spotlight-PBS

- Studio Spotlight-RLJ

- Studio Spotlight-Section 23

- Studio Spotlight-Severin

- Studio Spotlight-Shout Factory

- Studio Spotlight-Sony

- Studio Spotlight-Synapse

- Studio Spotlight-The Film Detective

- Studio Spotlight Turner

- Studio Spotlight-Universal

- Studio Spotlight Viz

- Studio Spotlight Warner Bros

- Studio Spotlight-Well Go Entertainment

- Zee Productions

Description

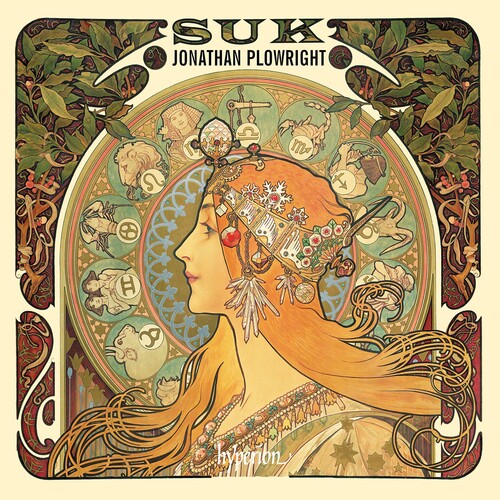

Suk: Piano Music on CD

For the Czech musical public in the early decades of the twentieth century, the names of two of Dvořák’s pupils, Vítěslav Novák and Josef Suk, loomed large. Within two generations, however, Leoš Janácek—at the time seen by Prague’s musical intelligentsia as a wild and woolly outsider from Moravia—is now incontrovertibly accepted as the leading figure in Czech music after the death of Dvořák. But perspectives shift and in the last thirty to forty years the music of Suk has begun to make its mark on concert repertoires across Europe. His string serenade in E flat major of 1892, much approved of by Brahms, is increasingly a favourite with conductors and audiences, as is his great ‘Asrael’ symphony.

In common with many Czech composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Suk’s origins were in a musical family from the Bohemian countryside rather than Prague. Tutored in his early years by his father, also Josef Suk, the school- and choirmaster of the small village of Křečovice, Josef junior soon moved on to the capital and from 1885 studied at the Prague Conservatory. He made remarkable strides in both composition and performance, staying on for a final year of study with Dvořák (who had joined the staff of the Conservatory in 1891) and graduating with an orchestral work, the Dramatic Overture, in 1892. Alongside his compositional activities, Suk specialized in chamber music with Hanuš Wihan, the leading Czech cellist of the day and the dedicatee in 1895 of Dvořák’s B minor cello concerto. This association led to Suk becoming the second violin of the Czech String Quartet in 1892, an appointment that initiated a busy, often international career as a performer that continued until his retirement over forty years later.

Suk’s links with the Dvořák family developed strongly through the 1890s and in 1898 he married the composer’s daughter Otilie (Otilka). Dvořák was an enthusiastic supporter of his career throughout this time; the sincerity of his interest can be gauged by a comment made to the composer and viola player of the Czech String Quartet, Oskar Nedbal, in which he described Suk’s incidental music to Julius Zeyer’s fairy-tale play Radúz and Mahulena as music ‘from heaven’. In fact, his music for Radúz and Mahulena, with its intense and abundant lyricism, was an expression of his profound love for Otilka. Her premature death in 1905, hardly more than a year after that of her father, was a devastating blow prompting a deepening of Suk’s style and a greater monumentality in his approach to form as can be heard in the ‘Asrael’ symphony and later orchestral works.

Given the similarity of their backgrounds and obvious personal affinity, it can be tempting to over-emphasize common stylistic traits in Suk and Dvořák’s music. But in fact their musical languages were quite different; one of the great qualities of Dvořák’s teaching was that he saw to it that his pupils were no mere imitators. Even in Suk’s early works there is considerable individuality in both melodic writing and his approach to structure. There is also a strong tendency toward expressive melancholy well before the dual tragedies of the deaths of Dvořák and Otilka.

The four groups of pieces for piano on this recording come from the first half of the 1890s (Opp 7 and 10) and 1902 (Opp 22a and 22b). Along with his professional engagement with the violin, Suk was an accomplished pianist, and from an early stage wrote with idiomatic confidence for the instrument in a series of works that often require considerable virtuosity. In inspiration, most of his piano music can be located firmly within the traditions of the romantic character piece. Along with such conventional designations as ‘Capriccio’ and ‘Romance’ found in the earlier sets of Opp 7 and 10, Suk also adopted the picturesque titles favoured by Schumann and also found in many of the solo piano collections of Smetana, Dvořák and Janáček.

Suk’s Op 7 collection of piano pieces is a gathering of individual works composed between 1891 and 1893, and first published as a whole in 1894. The first in order of composition is the concluding Capriccietto (originally entitled ‘Melody’); it begins with determination, but concludes on a reflective note. The next two to be written were the two Idylls. Originally entitled ‘Waltzes’, they were first published in 1893 as ‘Winter idylls’ (‘Zimní idylky’), dedicated to Nasťa Haškovcová, a friend of Suk’s sister Emilie, in an anthology of Slavic piano music assembled by the composer Zdeněk Fibich. Unquestionably waltz-like in rhythm, the first has a wistful quality sustained into the second where, after a more impassioned central section, the piano figuration seems to be evoking the sound of the cimbalom. From 1893, the Song of love (Píseň lásky), originally entitled ‘Romance’, was the last to be composed and is the longest of the set. After a languorous beginning, it develops passionately before a return to the sultry mood of the opening. The Humoresque is a brief, excitable waltz (its original title); it is followed by Recollections (Vzpomínky) whose opening may owe something to the start of the second movement of Dvořák’s ‘Dumky’ trio. After the Idylls, the first of the two remaining movements, Dumka, begins with the measured tread of a funeral march, but this is leavened by a delightfully open-hearted central section before the opening returns with even greater seriousness. Suk’s understanding of the ‘Dumka’ manner is very close to that of his father-in-law Dvořák: essentially, it involved the alternation of slow, thoughtful music with episodes of a more optimistic nature.

The group of five Moods (Nálady) which concludes this recording were composed between 1894 and 1895 and published by the Berlin publisher Simrock in 1896; they were dedicated to the Viennese pianist Clothilde Kleeberg who often played with the Czech Quartet. The opening Legend is expansive with a strong sense of epic narrative incorporating moments of almost Lisztian rhetoric. The Capriccio which follows is a poised and whimsical movement in Polka rhythm. The brief Romance at the heart of the set is characterized by surging melody often underpinned by exploratory harmonies. An understated Bagatelle leads to a racy, good-humoured finale entitled Spring idyll (Jarní idyla). As a whole this set impresses by its balance of both form and technique, not to mention the considerable demands it places on the performer.

The two cycles Spring (Jaro) and Summer impressions (Letní dojmy) were composed in 1902. Seven years on from the Moods, they were from a very different time in Suk’s life when early aspiration had given way to the contentment of marital bliss. Married to Otilka for four years, he had just experienced acute joy at the birth of their son—another Josef—an event that cemented his feelings of contentment and security. Nearly two decades later, he wrote to the musicologist Otakar Šourek about these years in which he produced music ‘of joy, full of love’. The reason both cycles share the same opus number (22a and b) derives from Suk’s original intention, made clear in a letter to his publisher, to produce four collections based on the seasons; unfortunately, he did not get around to composing Autumn and Winter.

The opening number of Spring communicates an almost uncontainable feeling of joy and lightness. The mercurial second movement is entitled The breeze (Vánek); Suk was an admirer of the music of Debussy and it is unsurprising to detect Impressionist colouring in the piano’s evocation of the caress of the wind. The remaining three pieces are united by a falling melodic figure, first heard just after the opening of the first movement. The third number, Awaiting (V očekávání), is perhaps the most conventional of the set while the fourth is the most enigmatic. Interestingly, in Suk’s original manuscript both the fourth and fifth movements were given the title Longing (V roztoužení), and were marked to be played ‘attacca subito’ without a break, but on publication the title of the fourth was replaced by three asterisks. What uncertainty seems to be present in this penultimate movement is resolved in the affirmation of the finale.

The three pieces of Summer impressions, composed shortly after Spring, were published the following year, although the public premiere did not take place until 1905. Suk was delighted that their first outing was given in Berlin by none other than Artur Schnabel, described by Suk in a letter to his Prague publisher, Mojmír Urbánek, as ‘one of the world’s greatest pianists’. Schnabel also included the fourth and fifth numbers of Spring. As a whole, the music of Summer impressions is rather more personal and original than that of Spring. The opening movement, At noon (V poledne), is both ear-catching in terms of piano sonority, outlining evocative open fifths, and speaks with a melodic simplicity that is both novel and individual. The two succeeding movements are again somewhat reminiscent of Debussy: the engaging opening of Children at play (Hra dětí) almost suggests that we are coming upon a scene already underway; Evening mood (Večerní nálada) explores more novel, occasionally modally inflected harmony extending still further the expressive frame of these remarkable pieces. Though relatively slight in scale, Summer impressions indicates how far Suk had developed from the accomplished if more conventional world of his piano music of the early 1890s.

Jan Smaczny © 2018